Abortion rights in the Czech Republic face a persistent challenge

By María Luz Nóchez

From street petitions to Parliament proposals, anti-abortion groups are working to shift public policy. Their efforts highlight a widening gap between legal rights and lived realities.

Samuel, Eliška, and Tereza were on their way to meet friends after school when they encountered a series of panels featuring images that they considered completely disturbing. When they approached the gentlemen at the information stand, they were asked to sign a petition to ban abortion in the Czech Republic. “We called the Police 30 minutes ago, and they haven’t shown up yet”, says Tereza, flustered by the lack of attention to their claim. They are 16 and 17 years old, and are upset to see younger children exposed to these images at the end of Masarykova, the main street that connects Karlovy Vary –the famous spa destination– with the city centre.

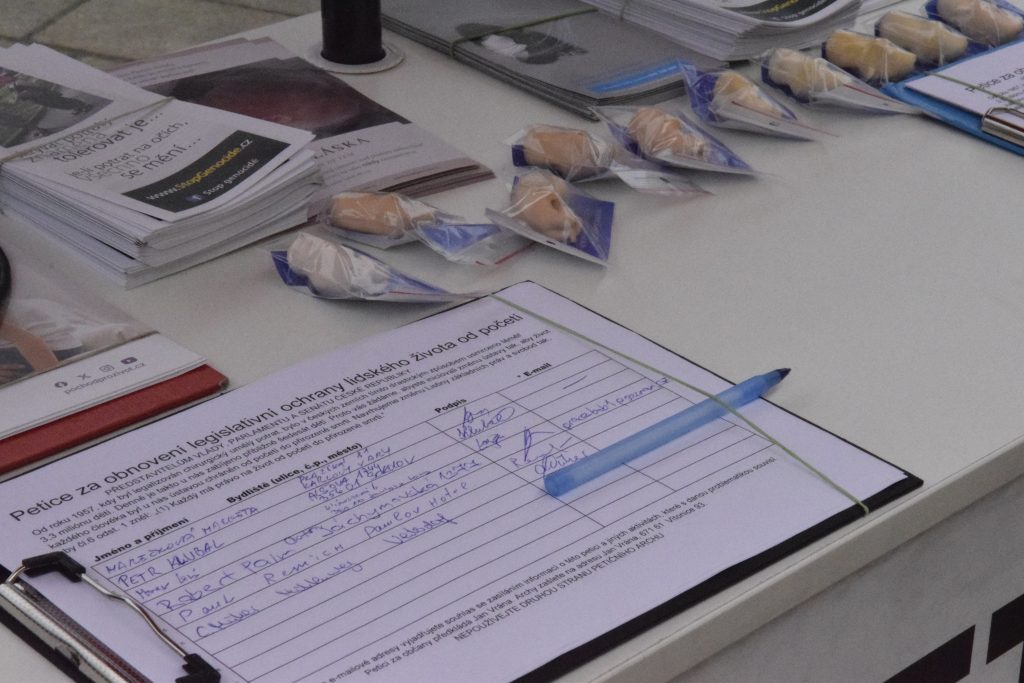

The panels display a series of pictures that compare human rights violations in, for example, Rwanda and the Nazi ocuppation, to abortion. The texts that accompany these pictures question how one can be socially accepted while the other receives global condemnation. The petition that the teens were asked to sign seeks “the constitutional enshrinement of the human right to life from the moment of conception”, eliminating the right to end a pregnancy, and any exceptions that might allow them to make that decision. Only five countries in the world have legislation like this one: El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Dominican Republic and Malta. A petition with 140,000 signatures was presented to the Senate in 2023 by the organizers of the exhibition, but was dismissed for not taking into account “women’s needs, their rights, and the social context.”

“If they don’t support abortion, they are in their right; what we don’t support is the way they are doing it with images so violent”, adds Samuel. For this group of friends, a future where abortion is not legal in the Czech Republic is scary, considering they have a friend in common who was able to interrupt a pregnancy at the age of 14. They were not alone.

Walking alongside the exhibition, several young people looked confused and disgusted by the pictures. Veronika, a 17 year old student let an effusive “what the fuck?” out of her mouth while she observed the panels. When explained that the exhibition is part of a petition to ban abortion in the Czech Republic, she frowns: “Abortion is a human right, why would you ban it?” A few minutes after her, Charli, a 17-year-old trans boy, also stopped to examine the panels. “For me, this could really matter because I don’t want biological children but if I somehow end up in that situation I’d like to have that choice”, says about the possibility of a future where abortion is not legal, adding that the obligation to carry a baby can worsen his body dismorphia. Having control over his body it’s also a matter of having a say in his future: “I don’t want to ruin my life and ruin someone else’s because I couldn’t have this choice.”

Photos 2 and 3. As kids stopped to contemplate the photos in the exhibition, teachers urged them to walk fast and keep their view to the front. / Jan and Petr engaged in discussion with angry passersby that vandalized one of the panels. 10 panels have been repaired along the years.

A traveling campaign aiming to rewrite the Constitution

Two men dressed in tactical clothing are the guardians of the exhibition, organized by the Stop Genocide Association. Jan Vrána and Petr (who did not provide his last name) have been traveling around the Czech Republic with the exhibition for years and are aware of the startlement their project brings to the cities they visit. The oldest record of the exhibition dates from September 24, 2008, in the city of Olomouc, in the eastern part of the country.

Banning abortion is a widely unpopular proposal in the Czech Republic. According to a 2023 survey by the Public Opinion Research Center (CVVM) of the Czech Academy of Sciences, 79% of Czechs believe that women should have the right to decide whether to terminate their pregnancies, marking the highest level of support since 1990. Only 2% of respondents supported a total ban on abortion.

Jan and Petr have experienced this in the field as people approach them to challenge their proposal and claim that there are more important issues happening. Sometimes, pedestrians instead cut the panels across. “We consider it important to be the ‚voice crying in the wilderness.’ It is necessary to constantly remind people of this, even if the majority does not accept it”, Jan explains.

For Petr, who joined the movement in 2015, there is satisfaction in bringing awareness about what he considers to be a problem, even when he has been confronted about being a man trying to restrict women’s bodily autonomy. “I would like to change one thing in the world –he says– and this is one of the opportunities.” Banning abortions, the World Heart Organization has explained, doesn’t prevent it from happening, but rather affects the safety and dignity of the procedures. For Petr, however, the goal is in reducing the numbers: “They won’t disappear, but maybe there will be 150 instead of 15,000 a year.”

When asked about affiliations with those in power who could promote changes in the Czech legislation, Jan says they have tried, but “there is no political will”. Both him an Petr say they have approached Jiří Čunek, a senator from KDU-ČSL (Christian and Democratic Union – Czechoslovak People’s Party), as well as representatives from the SPD and ANO. With the upcoming elections in October, they claim they have not reached out to anyone in particular, but believe Andrej Babiš could be “theoretically more inclined than others because he is conservative”, adds Jan.

Jan has been on the road with the panels since 2009 and claims the organization is just he and Petr. They work as volunteers and, according to Jan, they do not receive a salary. Their only compensation, they say, is accommodation and meals provided by people who host them in each city they visit. The website does not provide further information about the organization, and Jan is presented as the chairman and only contact. However, these panels are part of the Genocide Awareness Project (GAP), which is led by the Center for Bio-Ethical Reform (CBR), a US-based organization. Stop Genocide Association is one of their affiliates in Europe, where they also have a presence in Poland, Slovakia, Ireland, and the United Kingdom.

People’s rejection and the lack of political leverage would seem like reasons to believe Jan and Petr are, indeed, preaching to deaf ears. The Stop Genocide Association, however, does not stand alone.

Two movements, one goal: banning abortion

As much as Jan argues that the movements consist of just him and Petr, they are linked to the Movement for Life (Hnutí Pro život) through Radim Ucháč, the person who Jan identified as the one who invited him to join. Ucháč is the chairman of the Movement for Life, a long-lasting anti-abortion group founded in 1992. Before taking on this role, Ucháč was chairman of the Stop Genocide Association from 2008 to 2012, when he resigned from his membership. This is characterized by Czech scholars and feminist organizations as a PR stunt to distance the two movements and make themselves more pleasant for the public. “After undertaking several unsuccessful attempts to push through the political agenda, anti-abortion activists have altered their approaches”, explains Andrea Beláňová in an article that maps anti-abortion activism in the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

Photos 5&6: Children are a key prop used by the Movement for Life to make their message visible. Before taking the official picture of the event, the host asked for “the biggest number of kids” to take part.

“He (Ucháč) wanted the message to resonate among the Czech society, which is mostly atheist. The radicals from the Stop Genocide Association didn’t agree because they wanted to keep going with this brutal messaging, and they sort of separated, but they are still connected. They don’t say it publicly because it would delegitimize the Movement for Life, which presents itself as an emergency center for women who are pregnant and didn’t plan it”, clarifies Eva Svatoňová, a sociologist from the University of Jan Evangelista Purkyne.

Alongside an emergency help line for women with unwanted pregnancies, the annual March for Life has become its most significant activity. With a “We don’t judge, we help” motto, they have placed emphasis on the “natural happy family”, which they believe is the key to a healthy nation. In recent years, the marches, which once were a runway of white crosses walking down the city center of Prague, have been accompanied by banners with positive messages, like “Joy from Life” and “I am creative. I am pro-life.” These messages resonated with some Czech celebrities, who ended up promoting the event on social media. They even got the Czech President Miloš Zeman, the right populist, to officially support them in 2018.

Photos 7&8: Around 1500 people attended the March for Life 2025, including members of the clergy and nuns. While the movement no longer uses religious motives to congregate the group, some attendees prefer to bring them into the mix.

Ucháč refused to comment for this article, instead, he shared a press release in the days before the March for Life 2025, in which he insisted that they don’t focus on other social and political issues and refuse to be associated with them in any way. However, there is physical evidence that connects both organizations. For example, the car in which the panels of the Stop Genocide campaign travel across the Czech Republic belonged, up until 2015, to the Movement for Life, and the stationary Jan and Petr share with the public has either the logo of the Movement or the number of the emergency help line.

Unlike their partner organization, The Movement for Life has proven to have political leverage. “They work as assistants of MPs and somehow, they push their agenda through their network, which is very connected with the political conservative sphere that is in power”, adds Svatoňová.

Photo 10: Jiří Schwarz, rector of the Anglo-American University (AAU) used his time on the stage to say that climate change was not a problem for the Czech Republic, but demography is, as less and less children are being born every year.

In March 2025, they almost succeeded in pushing a reform proposal on public health insurance. The amendment aims to include a mandatory warning and referring to its website on every pregnancy test. MP Romana Bělohlávková (KDU-ČSL) proposed it, admitting to having heard the idea from The Movement for Life, as Seznam Zprávy reported.

“Legal doesn’t mean accessible”

This level of support coming from Parliament and professional conferences is not marginal, considering a similar initiative for spreading information about access to abortion was banned in the private sector in April. Jolanta Nowaczyk, co-founder of the Abortion Support Alliance Prague (ASAP), got a last-minute cancellation on the informational campaign she had been working on with MetroZoom since January. Knowing that abortion is still a taboo topic for some people in the Czech Republic, Nowaczyk made sure to ask the service provider if they were okay with the content of the posters, which included research-based information that fights myths against abortion “They accepted, we signed a contract, and when I sent the final files they decided to cancel the contract”, she explains. In order to make this campaign possible, ASAP organized a crowdfunding campaign to gather the money.

Nowaczyk was stressed out and upset, but decided to respectfully ask why. “The most shocking fact is that they said abortion is harmful primarily for fetuses. You cannot cancel a service based on something harmful to fetuses, because they don’t have rights!” This was a reminder for her on how overlooked the topic of abortion is in the Czech Republic, a stance that ASAP has been trying to change in the last years. “Legal doesn’t mean accessible”, she adds, and explains that when her collective started to research the availability of information about access to abortion in 2020, they realized the only available data was about how many abortions are performed per year in the Czech Republic. In contrast, they found that there is no State support for accessing an abortion and that the price for the procedure goes up to 20% of the minimum wage.

According to a report published in 2024 by ASAP, the cheapest place to undergo an abortion is the Hradec Králové Region, where surgical abortion (up to 12 weeks) costs 3,000 CZK (120.36 €) versus the Pardubice region, where the same procedure can cost 7,750 CZK (310.94 €). Regardless of the price, even when women are able to afford the procedure, some still face stigma from doctors, who refuse to give them a referral to have the treatment done, which carries an additional cost of 1,000 CZK (40 €).

The same document also reports that there is no consensus regarding the accessibility of these services for EU citizens without a permanent residence in the Czech Republic to have this treatment. Only 47% of hospitals contacted by the collective said they would take them as patients.

“The Czech Republic is considered a ‘paradise’ for women seeking to have an abortion, but without information on how to get one, it’s still far from it. Women should be informed about their options”, Nowaczyk adds. As a Polish national living abroad, she got involved in 2020 after the Court in her country ruled that abortions undertaken because of fetal defects are unconstitutional. “I got involved by rage. I was very upset”, she remembers. This is why for her the right to abortion should not be taken for granted, even if the support among Czechs is high. “The discourse of the Stop Genocide and the Movement for Life is manipulative and spreads misinformation, we must make knowledge accessible for everyone”.